The history of comics can be traced a long way back, all the way to ancient Japan. Illustrations accompanied by stories were not unusual. These first forms of comics were not created in order to be read by children; It was simply a way for people to note down incidents in their lives in a more vivid way.

The word, however, has long been associated with characters like Mickey Mouse and other similar culture icons. Comic artists and readers alike are more often than not criticized by “scholars” who look down on this specific form of storytelling and characterize it as childish and shallow. Hollywood movie adaptations of superhero comics have, with some exceptions, played a major role in forming the general public’s image of the medium. They are becoming more and more dependent on impressive special effects, undermining the serious messages of the original source.

This belittlement of the medium has only recently started to change as more mature content begun finding its way into the pages of comic books and as older works started being recognized for their literary depth and complexity. It takes only a simple look to the corresponding bookstore shelf for someone to realize that comics are not only meant to be read by children.

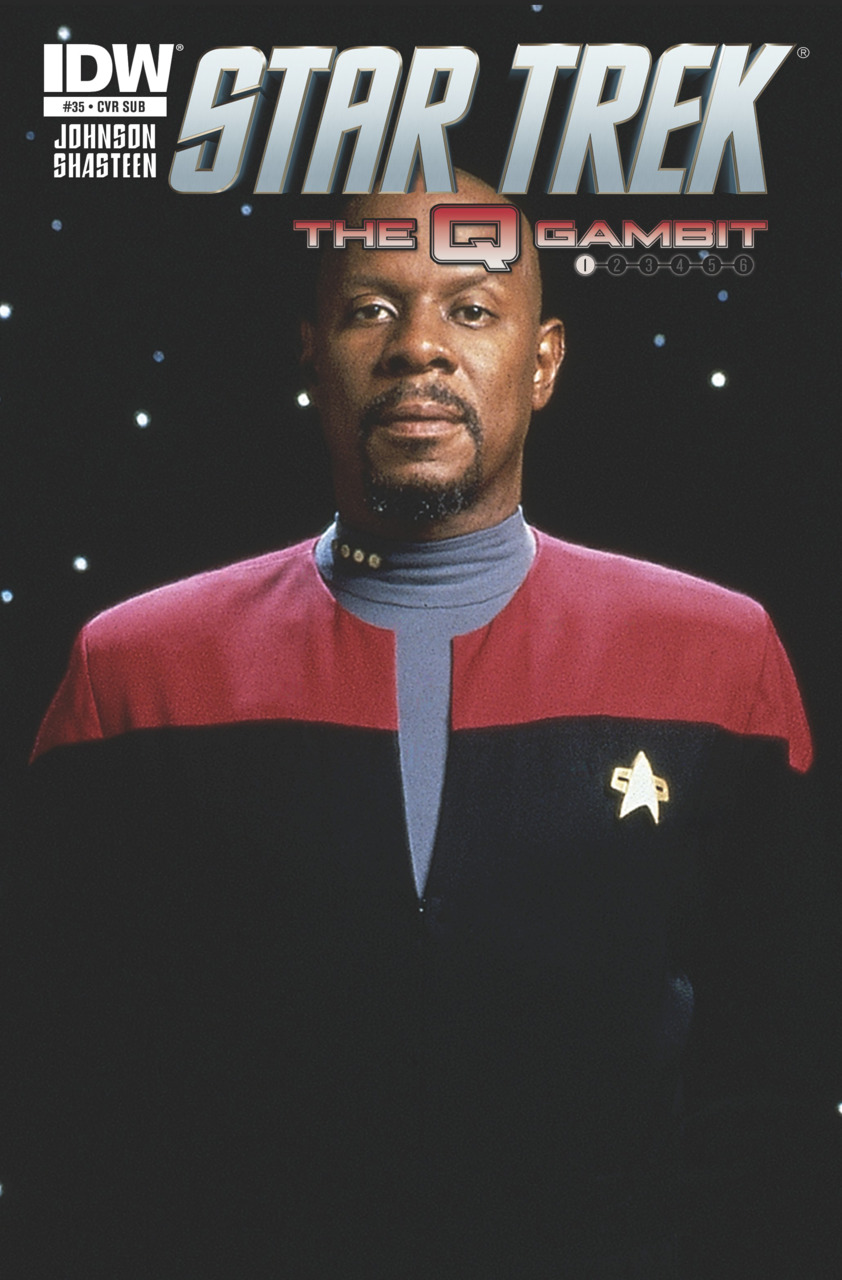

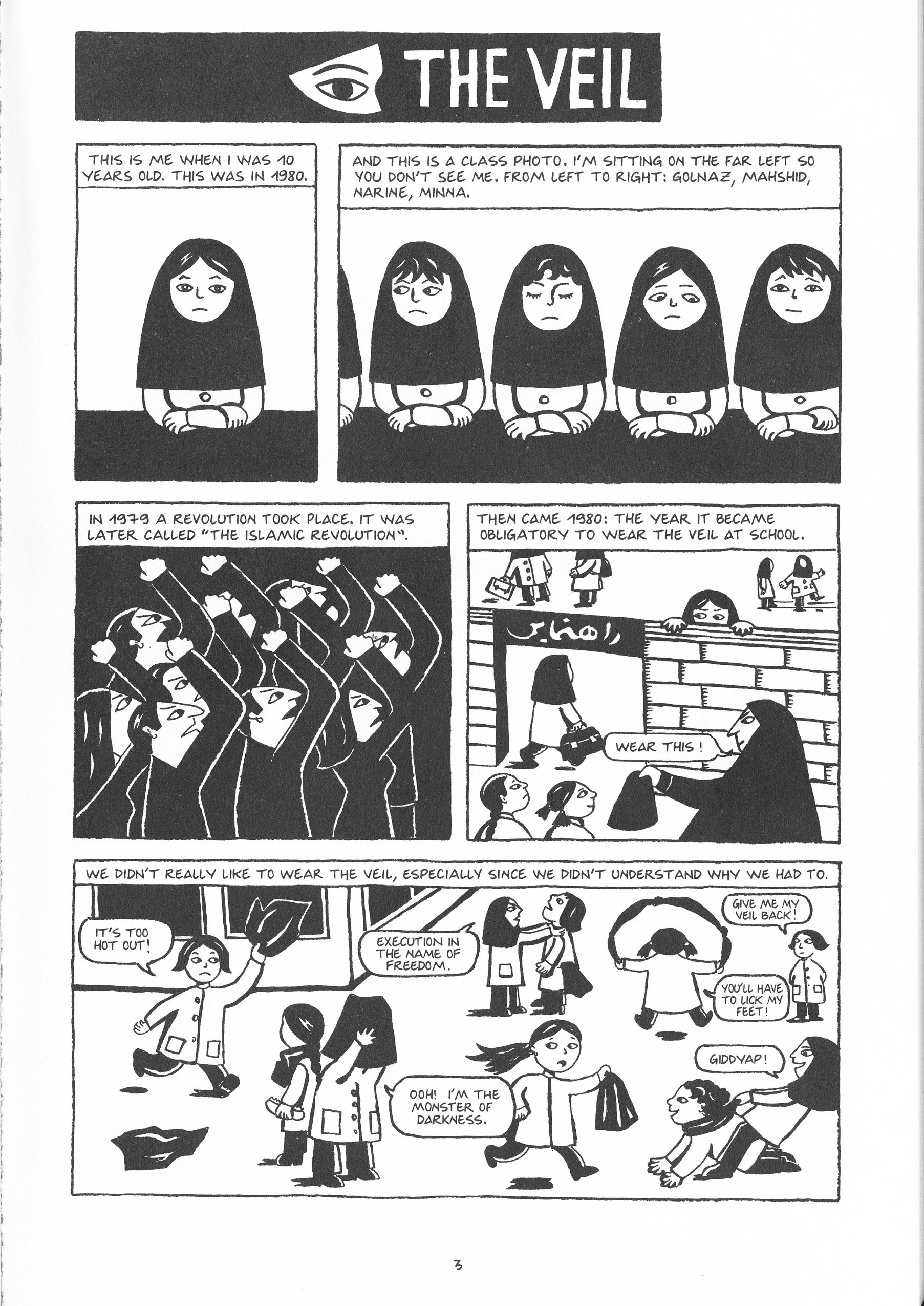

When one thinks about comics, the first thing that comes to mind is superheroes like Batman and Superman or Disney characters. Someone, however, that has come into contact with the culture of comics understands that there is much more to them than meets the eye. In the 80’s, works such as Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One; Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke; and Jeph Loeb’s Batman: The Long Halloween began re-inventing Batman. Along with many other books like Alan Moore’s Watchmen, they introduced a new view on the traditional superheroes of Marvel and DC Comics. They were much darker than before and the characters were acting according to the harsh reality and changes of their surroundings instead of following the invincible superhero trope. The psychology of the heroes became more central to the story, many times posing serious and difficult questions on identity, heroism and the structure of society. Nowadays, more and more graphic novels –another term for comic books which are usually longer- are debating current situations, such as ongoing wars and racial stereotypes. Joe Sacco, in his work Footnotes in Gaza, draws on conversations with Palestinians in two neighboring towns, regarding a series of conflicts, the reasons of which he tries to pinpoint in his book. It is clear that such a topic is not meant to be read by children. Marjane Satrapi presents through her autobiography Persepolis her childhood in Iran and the troubles she went through when she migrated to Austria alone, in order to escape from the fear of war and to continue her studies. She touches on topics such as stereotypes and religious laws as well as the oppression of women, issues that are constantly in the frontline. Alan Moore created V for Vendetta, a story that takes place in a corrupted society and focuses on V, a mysterious character that works against the “big brother” government. V for Vendetta was so relevant to current situations that it inspired the creation and symbol of a whole organization; Anonymous. Other artists like Neil Gaiman and Will Eisner work on other mature topics that would be deemed unsuitable for children. Just like books, articles and movies, comics have simply become another way for people to express their concerns and opinions of topics popular and controversial.

Marjane Satrapi, Persepolis, Source: http://knopfdoubleday.com/

One of the main reasons why comics are becoming more and more popular as a means of expression is the fact that the visual component, combined with the words can create more intense feelings for the reader than either of those would on its own. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. In collaboration with the text, the illustrations can convey a much bigger amount of details. A character’s facial expressions can depict his or her emotions much better than a word description would. Sometimes, the drawings are not very intricate but it is that simplicity which works together with the complexity of the words to create a very strong image. Persepolis and Footnotes in Gaza are a perfect example of this argument. Neil Gaiman’s illustrations in Sandman are much more detailed and that gives the story a whole other feeling of mystery and eeriness.

Alan Moore, V for Vendetta Source: http://www.comicvine.com/

It is that extra element, the fact that comic books can engage our sense of vision in a more challenging way, that makes them a unique kind of literature that is in many cases the most appropriate way to tell a story. And of course, there is not a specific amount of image and text that works for all types of narratives. The creator of a comic has to find a way to combine them in a way that serves the tale at hand. Rodolphe Töpffer, a Swiss artist whose work is considered to have influenced the shaping of comics form, says in his Essay on Physiognomics:

“To construct a picture-story does not mean you must set yourself up as a master craftsman, to draw out every potential from your material—often down to the dregs! It does not mean you just devise caricatures with a pencil naturally frivolous. Nor is it simply to dramatize a proverb or illustrate a pun. You must actually invent some kind of play, where the parts are arranged by plan and form a satisfactory whole. You do not merely pen a joke or put a refrain in couplets. You make a book: good or bad, sober or silly, crazy or sound in sense.”

That idea of the whole, the way in which the words and the ideas expressed through them complement the images and vice versa, is what makes a comic pull the reader in. It gives them the ability to search for the connection between the two components and interpret them in a new way. One might argue that the same thing happens with image and sound in a film. But the two mediums are very different. Comic books are not a continuous flow of pictures that appear and disappear in an instant. The reader can linger on each frame and word and that makes details and consistency important. Therefore, graphic novels have the ability to engage their audience in a way that requires mental work, even more so than a piece that consists simply of text, and “transfer” them into the story they are reading.

Comic books are being used more and more as a means for storytelling. The themes they present are starting to cross into journalism territory. The superheroes have been re-invented and reborn as more thoughtful, realistic and dark. Why then are they still considered “childish”? People that have not taken the time to engage with the comic book world associate them with the flashy, shallow characters that appear on the big screen or the lovely little mouse in red pants. But these are only a small part of the whole. Graphic novels are not only meant to be read by children. The medium itself is challenging both for the reader and the creator and should therefore be treated accordingly.

Sources:

- Williams, Paul, and James Lyons. The Rise of the American Comics Artist: Creators and Contexts. Jackson: U of Mississippi, 2010. Print.

- McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperPerennial, 1994. Print.

- McCloud, Scott. Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form. New York: Perennial, 2000. Print.

- Töpffer, Rodolphe, and Ellen Wiese. Enter the Comics: Rodolphe Töpffer’s Essay on Physiognomy and the True Story of Monsieur Crépin. Translated and Edited, with an Introduction, by E. Wiese. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965. Print.