When many cis men first read Wheel of Time, especially when they were younger, they thought of it as a translation guide. Surely, after reading so much about braid-tugging, internal monologuing, and polyamory that results in only one configuration (multiple women to one man), they must have a deeper insight about the gender they were told was their opposite.

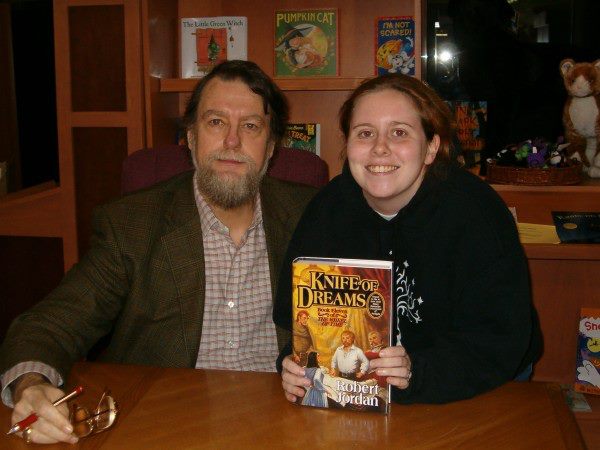

After all, Robert Jordan couldn’t be wrong. He had a wife! She was his editor! He totally interacted with a woman on a regular basis. That makes him an expert, right?

As a young cis woman, it was a complex and captivating read: powerful women, the Aes Sedai, get segmented and sorted into various Ajahs, represented by colors.

Each Ajah has a particular talent. How lovely that the amount of power and talents women hold is so great that there has to be a means of organizing it, right? But on the other hand, it’s an easy shortcut to see every woman as representing just one aspect of power, intelligence, or womanhood. If you’ve ever been a woman who attempted to deviate from what was expected of you, I’m sure you know what I mean.

Wheel of Time, in book form, is the best and the worst; empowering and objectifying; with flat characters and characters containing depth and exploring trauma. With 14 books and a prequel averaging 826 pages each, there’s room for a lot of conflicting information, especially since the series largely presents gender as a binary in some totally not kinky (but totally kinky) power struggle.

With the release of the initial three episodes Wheel of Time series on Amazon Prime Video, many of these same fans of course, well actually, knew that the show would suck trolloc bollocks long before we even saw cast photos. And once we did see the photos, well, of course Rosamund Pike is an inadequate Moiriane Sedai. As one fan-critic put it in a Facebook discussion group, “She looks the part, but she really isn’t tall enough.” Another said “she really doesn’t look ageless,” criticizing the conventionally attractive, mortal human actress who barely has any wrinkles yet still looks old enough to be wise.

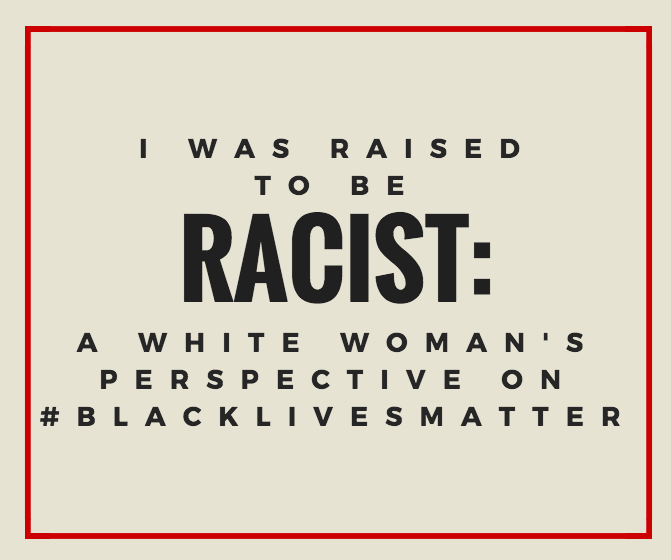

The loud fan-critics are especially clear about something else: “Social Justice Warriors are ruining everything!” by casting people of color in a world that was originally intentionally written as one of diversity primed for sheltered villagers to explore by necessity and for survival.

Being a woman on the outskirts of such a fandom, my experience never changed. It always centered men who “totally understand and respect the power of women” while simultaneously wielding sexism to shut down the viewpoints of most women.

The books, like my feelings towards author Robert Jordan are, complex: it was an empowering read, but also a harmful one. And, like a woman, a delightful read can be more than one thing. Wheel of Time helped me become a storyteller. Wheel of Time also filled me with a lot of internalized misogyny that took time to undo (and I’m still working on it).

Sexism in the Wheel of Time Fandom

It’s more obvious now that the show’s out, but for those new to these corners of the internet, you’ll find the following hallmarks of misogyny you’ll also see in popular fandoms like Star Wars:

- You’re wrong/not a real fan because I’ve been a fan longer!

- I know more facts/information than you, therefore I’m right!

- Despite the fact that it’s universally accepted that Rand al’Thor is an awful character, I relate to him because he’s the mediocre white guy who finally gets to take back his power!

- I hate it and can’t articulate why or will give you a false reason to show that I’m not just hating people of color and women of all colors, but I’m totally going to give this a 1 star rating on Rotten Tomatoes!

Blogger Johanna encapsulates this well in her post about the male protagonist of the series:

It would suck to go on a first date with Rand al’Thor – always talking about himself, never picking up on hints, alternating between needy and surly. He doesn’t know how to make Egwene feel pretty, even though it’s clear that she really cares about her hair and all.

This stuff isn’t new. It’s always been a problem. And Jordan, after all, did cast the universally whiny Rand al’Thor as his main man… one that other men unfortunately look up to because his burden of being different and awesome is just super relatable for the typical WoT reader–and he thinks about it when he’s not gatekeeping marginalized people from gaming stores and other fandoms, I bet.

Wheel of Time has always been that dirty not-so-little secret that I was simultaneously ashamed to like, but was universally praised by every geeky guy I dated for liking, whether said guy was a total jerk or a really supportive partner.

No, I Didn’t Want to Reread Wheel of Time Before the Show

That’s because it’s not a safe haven or point of nostalgia for me. When I heard there’d be real effort into producing an early Game of Thrones-quality Wheel of Time production, I was thrilled. However, I quickly realized that “fans” were ready to slam the show before it launched, for many of the reasons I outlined above.

I didn’t want to reread and encounter all of the problems the books would spin in my mind. I’ve worked years to overcome those tropes and stereotypes. Unlike fans who wanted to bask in the nostalgia, I was ready for the adaptation.

What Is a Book-to-Screen Adaptation?

Series like Wheel of Time and A Song of Ice and Fire (Game of Thrones) have masterfully shifting character perspectives. The authors help readers learn about the characters and their perspectives through the use of internal monologues, overt and subtle character interactions, and more. In addition to storytelling styles rendered more effective for novels, these books and their authors are products of their own experiences: their gender(s), the time(s) in which they wrote the books, and the influences on them by media, friends, family, and world events.

Robert Jordan started to write Eye of the World (the first book in the Wheel of Time series) in 1984. It was published in 1990. I am forty years old. When Robert Jordan began writing Wheel of Time, I was just learning to read (early) at age four. It’s safe to say that a lot has changed since then.

Since then, the world has faced multiple uprisings, wars, calls for social change, rising healthcare costs (especially here in the United States), and of course the global COVID-19 pandemic. This context matters.

Any successful show, particularly an adaptation, needs to speak to the experience of the audience. While it’s useful to have an exercise in empathy by learning about characters who are different than us, it helps us to connect with said characters when we have common experiences. In the case of the show, the show runners decided to highlight a tale of prosperous and successful people who failed because they didn’t work together, as well as the fear and suspicion common people feel when a woman with stated power (Aes Sedai) rolls into town.

As a viewer who has experienced these things, it really helped me relate to the characters.

Media Arts instructor Dan Watanabe outlines the process of book to film adaptation here:

“The better a book is, as a piece of literature, the less likely it is to make a good movie,” he says. Watanabe provides The Great Gatsby as an example. He also offers Jaws and The Godfather of examples of books that weren’t so great, but translated into great movies. He says that’s because “screenplays are very direct.”

Later in this informative video, Author Solutions’ Former Director of Media Services Caroline Weiss says “a well-developed story with really strong characters” makes for the best book to screen adaptation.

Looking at the Wheel of Time series, it really fits the bill. There are over 100,000 characters in the series, and the initial group we meet in the first book (and in Episodes 1-3) experience immense character development. Filmmakers and actors don’t need a super and accurate detailed representation of a character: they need a straightforward, solid template. They don’t need the most masterfully written content, they need the key beats. No slight intended towards the author himself–but the Wheel of Time series is ideal. Its strongest fans often admit its obvious flaws.

To be a success, a long-running fantasy epic like Wheel of Time or Game of Thrones needs to meet the following marks:

- Emotionally, practically, and intellectually accessible for a popular audience

- Enough hints, nods, or Easter eggs to please the long-time fans

- Gripping and event-filled enough to sustain audience interest and discussion over a long amount of time

- Different enough from the source material to be different, but close enough to resonate with the spirit of the story

- Presenting themes that overtly or subconsciously cause viewers to relate due to a comparison with the here and now

- Diversity of characters (not only in race, gender, sexuality, and more, but including that) to reflect a rich fantasy setting and to engage audiences living in the real world

- Studio support, wide distribution, and a lot of money

A lot of old-school fans don’t seem interested in educating themselves on this topic. While I am a written, verbal, and business storyteller expert, I don’t know much about film studies–so above, I did what they should do. I researched.

What Makes Wheel of Time Work

In addition to conforming to the aforementioned successful fantasy adaptation points, the Wheel of Time series visually represents elements that are both important to the story and the source material, as well as relatable to some or all members of the audience.

Among the fandom and in the book, the concept of braids in women’s hair, particularly Nynaeve’s, becomes a trope and a joke. In the book, Nynaeve (played by Zoe Robins, seen on the left in the photo) constantly expresses worry or anxiety by tugging on her braid. Even the book’s fiercest fans joke about how ridiculous this is, and that Jordan did a poor job of representing this particular woman.

In the Amazon version of Wheel of Time, we see this phenomenon addressed immediately. In Two Rivers, the braid represents ascension to womanhood. A recently braided woman can make her own decisions about sex, partnership, and career, and it’s implied that’s the age when it’s acceptable to start consuming alcohol as well. A braid isn’t something to make fun of here, but something to be proud of, recognized by all members of the village–and it wasn’t lost on me that village Wisdom Nyneave not only models this tradition and teaches it to others, she is portrayed by a New Zealander of Nigerian descent. (While this is imperative for me to express, it isn’t my subject to speak on. Learn more about the importance of hair and representation for Black women and their characters from TeenVogue author Jameelah Nasheed and TZR author Bianca Gracie.)

Immediately Represented Ethnic, Cultural, and Global Diversity in Wheel of Time

As an audience member who has read the book, this is an obvious indication that the show is not here to conform to tropes or inaccuracies when it comes to women characters, and that it’s also not here to entertain the racism many “original fans” have been displaying as “displeasure with the casting.” Powerful women full of potential are front and center early on, represented by women of multiple ethnicities.

Additionally, we have already seen multiple shots and scenes featuring women of multiple ethnicities, including mix-race ethnicities. The world presented in Wheel of Time, even in the books, has always been about people from various parts of it; specifically, the Aes Sedai come from all over to be tested at and trained in the White Tower. Clearly the show is strongly reflecting that.

That many fans take it as a “political statement” that the show represents what the books described and implied reveals the inherent racism in the “original fan community.”

Note: While the show telegraphs decisions about racial equity and the power of women, we have yet to see how it will handle topics like why gender is binary and what place nonbinary and trans characters have in this world (if any). Clearly, the potential is there for the show to explore this–it’s about gender and power! But will it?

Are Revelations About Toxicity in the Wheel of Time Fan Community New?

For marginalized readers, the resurgence of gatekeeping, racism, and sexism are no surprise. These unfortunate features of fandom have unfortunately always existed, and will continue to exist in the name of “everyone being able to have their own opinion.” And while power is complex for anyone like me, who read the books as a young woman, we all know that the most powerful characters are largely focused on ensuring that while certain events come to pass, the world (hopefully) does not break.

But, you know, some people don’t see that systemic oppression is already breaking the real world, so they just want to gatekeep the community and force their opinions on others and discourage the new fans that, with a renewed approach, will keep the spirit of the series alive.

Having listened extensively to the author before his passing, my take on RJ is that he’s a very classic case of intending well, but not always impacting in a helpful or positive way. I definitely wouldn’t argue that his ideas are progressive or that he’s a hero for entertaining the idea of a female fantasy protagonist (rather imperfectly). However, this series is undoubtedly his life’s work and I think he’d be pleased with and honored by how it’s been represented in these first three episodes.

A real storyteller understands that the value of a good story is its ability to adapt with the times and remain relatable to an audience. That’s what keeps it alive, and what gives the author or culture of origin a chance at a legacy.